Language change; languages of the world (historical linguistics and linguistic typology)

The puzzle of language change

In the next lecture we will look at sociolinguistics, and we'll see that language varies across geographical space and across social group. Indeed, variation is apparently an inherent characteristic of human language -- something which separates it from most other forms of animal communication.

Similarly -- and perhaps for the same reasons -- language is constantly changing. Generation by generation, pronunciations evolve, new words are borrowed or invented, the meaning of old words drifts, and morphology develops or decays. The rate of change may vary from age to age and place to place, but it never stops.

When populations initially speaking the same language come to be separated, the changes that their speech undergoes cease to be shared. As a result, such subgroups will drift apart linguistically, and eventually will not be able to understand one another.

In fact, language change is often socially problematic. Long before divergent dialects completely lose mutual intelligibility, they begin to show difficulties and inefficiencies in communication, especially under noisy or stressful conditions. Also, as people observe language change, they usually react negatively, feeling that the language has "gone down hill" or "decayed". You never seem to hear older people commenting that the language of their children or grandchildren's generation has improved compared to the language of their own youth.

This presents us with a puzzle: language change is functionally disadvantageous, in that it hinders communication, and it is also negatively evaluated by socially dominant groups. Nevertheless it is a universal characteristic of human language and, for the most part, cannot be stoped.

How and why does language change?

There are many different sources of language change. Changes can take originate from language learning, or through language contact, social differentiation, and natural processes in usage.

Language learning: Language is unavoidably transformed as it is transmitted from one generation to the next. Each individual must re-create a grammar and lexicon based on input received from parents, older siblings and other members of the speech community. The experience of each individual is different, and the process of linguistic replication is imperfect, so that the result is variable across individuals.

Think of the game people -- especially children -- play at parties, where one person whispers a sentence to the person sitting beside them, that person in turn whispers it to the person beside them and so on, through a chain of listeners and speakers, until the last person who says it aloud for everyone to hear. Typically, the end result is garbled beyond recognition from the original by the sequence of imperfect transmissions. This is essentially how language learning works, although over a much longer time scale, with a far more complicated and abstract message and a much higher level of success.

A bias in the learning process -- for instance, towards regularization or paradigms (e.g. the replacement of older holp by helped) -- can cause systematic drift, generation by generation, but frequently, the mutation of a language through imperfect learning is essentially random.

Language contact: Migration, conquest and trade can bring speakers of one language into contact with speakers of another language. Some individuals may become bilingual as children, speaking both languages natively, while others may learn the second language more or less well as adults in order to conduct business, interact with neighbors and the like. In such contact situations, languages often borrow words, sounds, constructions and so on.

Social differentiation. Social groups adopt distinctive norms of dress, adornment, gesture and so forth; as we saw in the last lecture, language is an important part of the package. Linguistic distinctiveness can be achieved through vocabulary (slang or jargon), pronunciation (usually via exaggeration of some variants already available in the environment), morphological processes, syntactic constructions, and so on.

Indeed, it seems that many instances of language change, especially those which differentiate one dialect or language from another, start out as markers of some social group. And sociolinguistic research has shown that all changes have a social dimension while they are in progress, with one social group or another leading the change and others following behind.

Natural processes in usage. Rapid or casual speech naturally produces processes such as assimilation (pronouncing neighboring sounds more like each other), dissimilation (pronouncing neighboring sounds less like each other), syncope (eliminating a vowel in the middle of a word) and apocope (eliminating a vowel at the end of the word). Through repetition, particular cases may become conventionalized, and therefore produced even in slower or more careful speech.

Certain changes arise from pressure to maintain a certain amount of symmetry in the linguistic system. This is especially the case in changes in vowel systems. If one vowel changes its pronunciation significantly, it often pulls the rest of the system with it.

Word meanings can change in a similar way, through conventionalization of processes like metaphor and metonymy. For example the meaing of trivial has gone from "pertaining to the trivium, the elementary areas of study" to "simple or easy to the point of being meaningless". This was originally a metaphorical extension, but the word came to be used in this way so often that it has completely lost its unextended sense.

But why?

So we have some pretty good answers as to how language changes, but we haven't made clear why it should change. Social differentiation is clearly important, and it's clear that the process of language learning is going to have important effects if it is not perfect and deterministic, and it's even clear that the internal pressures of the system might have some effects, but some mysteries remain.

For one thing, why must language be learned at all? If we have a languange instinct, as Pinker and Chomsky argue, then why aren't we just born knowing all of the details of language? Then everyone would have the same language, we could all talk to each other, and children wouldn't have to spend so much time in their formative years learning to speak. Pinker argues that there are evolutionary reasons favoring the current situation -- where the blueprint for language is instinctive, but the details are learned. For one thing, this allows flexibility and extensibility, for example the creation of new words for new concepts. For another, it provides a way for people to sync up their languages in the case that, by some genetic mutation, their language instincts diverge somewhat.

We might also wonder why the inernal pressures of the system and for ease of articulation don't eventually push a language into some perfect state where pronunciation is as easy as possible, and the system is perfectly symmetrical. The reason for this is that the pressure for ease of pronciation is counteracted by pressure for ease of understanding. A maximally easy pronunciation of a language would also be maximally incomprehensible. Changes resulting from internal pressures actually seem to be a constant balancing act, an attempt to maintain an equilibrium that is being constantly disturbed by other changes.

The analogy with evolution via natural selection

Charles Darwin himself, in developing the concept of evolution of species via natural selection, made an analogy to the evolution of languages. In fact, he explicitly noted that some of his ideas on the descent of species were inspired by the linguistic ideas of his day. For the analogy to hold, we need a pool of individuals with variable traits, a process of replication creating new individuals whose traits depend on those of their "parents", and a set of environmental processes that result in differential success in replication for different traits.

We can cast each of the just-listed types of language change in such a framework. For example, in child language acquisition, different grammatical or different lexical patterns may be more or less easily learnable, resulting in better replication for grammatical or lexical variants that are "fitter" in this sense.

The general idea is that at any given point in time within a population, there is a certain amount of variation, where some variants survive to the next generation and others are eliminated, the overall effect being a drift from some older set of characteristics defining the group to a newer set of somewhat different characteristics.

At certain points, for any number of reasons, portions of the community will split off, losing contact with one another. From this point on, they will drift in different directions, until at some point they can no longer be considered a single population. In evolutionaty terms, different species are formed at the point where individual members of the one population can no longer mate and breed successfully with an individual member of the other population. In linguistic terms, different languages are formed at the point where members of the two populations can no longer understand each other.

There are some key differences between grammars and genotypes. For one thing, linguistic traits can be acquired throughout one's life from many different sources, although intitial acquisition and (to a lesser extent) adolescence seem to be crucial stages. Acquired (linguistic) traits can also be passed on to others. One consequence is that linguistic history need not have the strict form of a tree, with languages splitting but never rejoining, whereas genetic evolution is largely constrained to have a tree-like form (despite the possibility of transfer of genetic material across species boundaries by viral infection and so on).

Still, as a practical matter, the assumption that linguistic history is a sort of tree structure has been found to be a good working approximation. In particular, the basic sound structure and morphology of languages usually seems to "descend" via a tree-structured graph of inheritance, with regular, lawful relationships between the patterns of "parent" and "child" languages.

Types of Change

All aspects of language change, and a good deal is known about general mechanisms and historical details of changes at all levels of linguistic analysis. However, not all types of change are equal in this respect, as we shall see. We can think about this in terms of changes in subparts or modules of the grammar, in the syntax, the phonology, the semantics and the morphology.

Semantic drift

Semantic changes usually take the form of drift in the meaning of a particular word, sometimes randomly, but usually on a roughly metaphoric path, like that of trivial described above.

Because such changes affect specific words rather than larger grammatical classes, they are usually not terribly systematic. That is, while we can talk about types of semantic change that are more or less likely, we cannot usually make broad statements about semantic changes within a given language.

Syntactic change

The structure of sentences within a language changes over time as well. For example, a number of European languages have gone from being primarily SOV to being SVO during their recorderd histories, including English and the Romance languages. Sentence a), for example, taken from the early Old English poem Beowulf, has the verbs at the end of the clause, where the modern English translation in b) has them in the middle:

a) ac he sigewæpnum forsworen hæfde

b) but he had forsworn (put a spell on) the victory-weapons

Syntactic changes of this sort are a good deal more systematic than semantic changes, because they affect not specific sentences, but entire rules of the grammar. Some of the foundational work on syntactic change has been done here at Penn by Anthony Kroch (currently the chair of the linguistics department) and his students, and if you're interested in such things, you can take Ling 310, Linguistic History of English, which he co-teaches with Don Ringe.

Sound change

While we have begun to understand syntactic and semantic change fairly well over the past few decades, the biggest success story in hitorical linguistics (and perhaps in linguistics in general) is in our understanding of sound change, i.e. the ways that pronunciations and phonological systems change over time. This is in part because high-quality research on this area has been going on for well over a century, but partly also because of the nature of sound change itself.

In the cases where we have access to several historical stages -- for instance, the development of the modern Romance Languages from Latin -- it turns out that sound changes are remarkably regular. This is because, in general, sound changes do not affect individual words, but phonological systems. For example, speakers in Philadelphia haven't just started pronouncing out more like [eot], they have started pronouncing the sound /aw/ like [eo] everywhere it occurs.

In some cases, an old sound becomes a new sound across the board, in every phonological environment. We call these unconditioned sound changes.

One example of an unconditioned sound change, which occurred between Middle and Early Modern English (around Shakespeare's time), is the upheval known as the Great Vowel Shift. In earlier stages of English, there was a length distinction in the English vowels, and the Great Vowel Shift altered the position of all the long vowels, in a giant rotation.

The nucleus of the two high vowels (front "long i" /i:/, and the back "long u" /u:/) started to drop, and the high position was retained only in the offglide. Eventually, the original /i:/ became /ay/ - so a "long i" vowel in Modern English is now pronounced /ay/ as in a word like 'bite': /bait/. Similarly, the "long u" found its nucleus dropping all the way to /au/: the earlier 'house' /hu:s/ became /haus/. All the other long vowels rotated, the mid vowels /e:/ and /o:/ rising to fill the spots vacated by the former /i:/ and /u:/ respectively, and so on. That is why the modern pronouns 'he' and 'she' are written with /e/ (reflecting the old pronunciation) but pronounced as /i/. In the following chart, the words are located where their vowel used to be pronounced -- where they are pronounced today is indicated by the arrows.

In other cases, a sound change may be "conditioned" so as to apply in certain kinds of environments and not in others. One such change, which is very recent, is the flapping pronunciation of /t/ and /d/ in American English which we discussed before. At an earlier stage of the language (and at present in other dialects), all instances of /t/ were pronounced more or less the same, as [t], and the same goes for /d/. Recently, however, a new pronunciation, which we've represented as [D], has arisen, but not for every instance of /t/ and /d/. Rather, this change has only occurred when the sound is before an unstressed vowel in non-word-initial position. Note, crucially, that while such a change is not across the board, it is nonetheless completely regular according to rules that can be formulated in purely phonological terms. This is the power of sound change.

Indeed, the understanding of conditioned sound changes was one of the defining insights in the history of linguistics. The beginnings of comparative and historical linguistics lie in the 18th century, when it was first recognized that Sanskrit, the ancient sacred language of India, must somehow be related to the classical languages of Europe, including Greek, Latin and Gothic among others. As scholars began to compare the languages in detail, they found that they could make broad statements about correspondances between the languages. For example, Jacob Grimm (yes, the guy who wrote the fairy tales), following a Danish linguist named Rasmus Rask, noted that the Germanic languages (including German, Dutch, English, Norse and the extinct language Gothic) tended to have fricatives where the other languages had voiceless stops, as in the following examples (I use English examples for Germanic and Latin for non-Germanic):

| English | Latin |

| father three hund(red) |

pater tre:s centum |

On this basis, it was possible to formulate sound correspondances between languages, and to theorize the sound changes that might have led to the differences. So, in what came to be known as Grimm's Law, we have rules like Indo-European *p > Germanic *f and so forth. (We use * to mark forms that are not attested anywhere, but have been reconstructed for some pre-historic period. That is, on the basis of what we know about certain attested languages, we hypothesize a form for their parent language. Do not confuse this with the * which markes ungrammaticality!)

It was originally thought that these expressed tendencies, not absolute rules, because a certain number of exceptions could be found, like the following (where necessary, I've given Gothic examples instead of English):

| English | Latin |

| stand fisk (Goth.) played (past participle) fader (Goth.) |

sta:re piscis ama:tus pater |

In the first two words we have a voiceless stop in the Germanic words just like in the Latin word. In the second two we have a voiced stop. In both instances we would have expected, on the basis of Grimm's Law, to have a voiceless fricative.

However, it was discovered in the late 19th century that the apparent exceptions to Grimm's Law fall into phonologically-defined classes. So the first two above happen to follow /s/, and indeed in all instances where an Indo-European stop followed an end, it remained a stop rather than becoming a fricative. This is not surprising if we think about what happens to stops after /s/ in Modern English.

With the other two examples, it turns out that, in the original language, the word stress was on the syllable following the voiceless stop. For example, the Sanskrit word for "father" is pitá, and the Greek word is paté:r. Similarly, the participle had stress on the suffix, not the stem. Indeed, it turns out that all non-initial /p,t,k/ which were followed by a stressed syllable came out as /b,d,g/ in the Germanic languages rather than /f,th,x/.

Grimm's Law was thus reformulated by a linguist named Verner (and thus is now sometimes called Verner's Law), as a conditioned but exceptionless change. At around the same time, a series of sound changes were understood in this way, with their exceptions being eliminated by more detailed formulation of the phonological environment. The linguists of this era called themselves the Junggrammatiker or Neo-Grammarians, and proposed the theory that all sound change is regular.

Processes of sound change.

Sound changes can be classified according to the particular process involved.

Assimilation, or the influence of one sound on an adjacent sound, is perhaps the most pervasive process. An extremely common assimilation process is responsible for the variation in how the prefix in- is pronounced. Before alveolar consonants and vowels it is simply [in], as in intractable and ineligible, but before velar consonants it usually takes on a velar pronunciation, as in incredible, which in fast speech usually starts with [iŋcr-], and before bilabial consonants it has the bilabial pronunciation [im], which is actually reflected in the orthography, as in impossible.

In contrast to assimilation, dissimilation, metathesis, and haplology tend to occur more sporadically, i.e., to affect individual words. Dissimilation involves a change in one of two 'similar' sounds that are adjacent or almost adjacent in a particular word to make them less similar. For reasons that are not entirely clear, this mainly affects /l/ and /r/. Thus the first "l" in English colonel is changed to an "r", and the word is pronounced like "kernel".

Metathesis involves the change in order of two adjacent sounds. For example Modern English third is from OE thrid , and Modern English bright underwent the opposite change, its ancestor being beorht. But this is not a regular sound change. Not all "vowel + r" words changed the relative order of these segments, and sometimes we get variation in a single word. Already by the time of Old English, there were two forms of the word for "ask": ascian and acsian. We don't know which form was metathesized from the other, but we do know that ascian won out in the standard language, while the descendent of acsian lives on in many non-standard dialects.

Haplology is similar to dissimilation, because it involves getting rid of similar neighboring sounds, but this time, one sound is simply dropped out rather than being changed to a different sound. An example is the pronunciation of Modern English probably as prob'ly.

Other sound change processes are merger, split, loss, syncope, apocope, prothesis, and epenthesis. Merger and split can be seen as the mirror image of each other. A merger that is currently expanding over much of the United States is the merger between "short o" and "long open o" in words like cot and caught which we've discussed in previous lectures.

Splits are more rare than mergers, and usually arise when a formerly conditioned alternation loses the environment that provided the original conditioning, and the previously conditioned alternation becomes two independent sounds that contrast with each other. This is basically what happened when /f/ and /v/ split in English (/v/ having previously been an alternate of /f/ when /f/ occurred in an intervocalic position). Plurals like loaves and leaves to loaf and leaf are reflexes of this old alternation.

Loss involves the loss of a sound from a language, as when English lost the velar fricative [x] (like the ch in German Bach, which is still written in some words as gh (e.g. bright, night, rough).

Syncope and apocope are the loss of medial and final sounds respectively. Middle English 'tame' in the past tense was /temede/. It lost both its medial and final vowels to become Modern English /teymd/. These are usually conditioned changes that do not involve loss of the same sound elsewhere.

Prothesis and epenthesis are the introduction of additional sounds, initially and medially respectively. The addition of the /e/ that made Latin words like scola 'school' into Portuguese escola is an example. As for epenthesis, an example from English is the /d/ inserted into ME thunrian to give us the Modern English thunder, or the short vowel inserted in front of the inflectional suffixes -s and -d when they follow similar sounds.

It was mentioned above that one of the motivations for language change is the pressure to maintain a symmetrical system. What does this mean?

The most common example of this is where the vowel system of a language goes through some sort of adjustment to maximize the differences between the various vowels. There is a clear functional motivation for this: in order for a language to be easy to understand, the individual sounds it is made up of should be maximally distinct from each other. If two vowels are pronounced very similar to one another, there will be a relatively high frequency of misunderstandings, where the speaker intends one vowel, but the hearer understands another.

Of course, speakers are not directly conscious of exactly where they pronounce their vowels, not do they think about spreading out their vowel pronunciations, so it would be hard to argue that speakers are consciosly modifying their speech in this way to make sure that their conversational partners understand them. So how is the pressure to spread out the vowels actually realized?

Labov talks about this in the article I assigned for reading this week, and proposes a very attractive account.

The techniques that have been developed to deal with sound change, combined with certain important assumptions, permit us to reconstruct the sound system -- and some of the vocabulary -- of unattested parent languages from information about daughter languages. For example, on the basis of the Gothic, Greek and Sanskrit forms of the word for father, and given certain knowledge about what sorts of sound changes are likely, we can hypothesize that the word for father in the language that was the common ancestor of all of these languages was something like *pxtér. In fact, over the past 130 years, a great deal of the phonology, morphology, vocabulary and even the syntax of this language, which we call Proto-Indo-European, has been reconstructed, and we can be confident that our reconstructions are fairly accurate, even though PIE was spoken about 6,000 years ago and has no written legacy.

Analogy

Another common type of change which breaks up historical regularity in favor of synchronic regularity is analogy. This is most frequently a morphological change, where the inherited form for some category is replaced by a form which has been extended from some slightly different category. Usually, this is the way in which irregularities are levelled out.

An example of this is the creation of the form helped to replace the older holp. The ending -ed was extended to this verb on analogy with other regular verbs in the language, like played and worked.

How do we know how languages are related?

As mentioned above, linguists rely on the regularity of sound changes to reconstruct the common ancestor of languages they know to be related to one another. But they also rely on this to establish in the first place that two or more languages are related and how the relationships work.

In order to figure out whether two languages are related, we attempt set up regular sound corresondences between them. That is, we look for pairs of words that look like cognates, i.e. words that descend from a common word in an ancestral language, and we figure out whether there are consistent patterns of one sound in language A corresponding to one sound in language B.

This can be easily done for English and German, two fairly closely related languages. In fact a great number of specific correspondences can be listed, but for brevity I will restricti attention here to some of the initial consonants.

So at the beginning of a word, the English stop /p/ corresponds to the German affricate /pf/.

| path | Pfad | pan | Pfanne | pepper | Pfeffer | |||

| pipe | Pfeiffe | plant | Pflanze | plum | Pflaume |

Corresponding to English /t/ at the beginning of words, German has the affricate /ts/, written as z.

| tame | zahm | to | zu | tongue | Zunge | ||||

| ten | zehn | twenty | zwanzig | tin | Zinn |

Initial /d/ in English corresponds to German /t/:

| day | Tag | dance | tanzen | dew | Tau | ||||

| devil | Teufel | drink | trinken | do | tun |

And finally, initial English /th/ correspond to German /d/:

| that | das | thick | dick | thin | dünn | ||||

| thirst | Durst | three | drei | though | doch |

If we can set up sound correspodences like these for a pair of languages, then we can reasonably say that they must be related, in the sense of being descended from a common ancestor.

This is because the probability of such consistent and extensive patterns arising either by chance or due to borrowing from one language into the other are vanishingly small.

In instances where we can observe it in the historical record -- say from Latin to the various Romance languages -- sound change leaves precisely these sorts of patterns, thus the most likely hypothesis is that English and German are descended from a common source.

Once we have correspondences like this, we can try to figure out the original sound and the sound changes that derived the attested sounds from it in each language. When we have more than one language to compare, we can also use this method to figure out interrelationships within the larger group.

The basic idea is that when a change occurs within a speech community, it gets diffused across the entire community of speakers of the language. If, however, two communities have split and are no longer in contact, a change that happens in one community will not get diffused to the other community. Thus a change that happened between early and late Latin would show up in all the 'daughter' languages of Latin, but once the late Latin speakers of the Iberian peninsula were no longer in regular contact with other late Latin speakers, a change that happened there would not spread to the other communities. Languages that share innovations are considered to have shared a common history apart from other languages, and are put on the same branch of the language family tree.

For example, we can recognize that English, German and Gothic are all Germanic languages, because they all have /f/ as the first sound in words meaning "father", "five" and "for", a trait which distinguishes them from the other Indo-European languages, which have a /p/ in this position (cf. Greek pater, pente, pro:). The sound change *p > *f is a shared innovation of the Germanic langauges.

We can further tell that German and English form a group to the exclusion of Gothic because, e.g., they have /r/ sounds where Gothic preserves the older Germanic /z/, as in English more and German mehr vs. Gothic maiza. That is, the sound change *z > *r is a shared innovation of what are called the West Germanic languages.

We can further tell that the Bavarian and Alemannic dialects of modern German (which are not mutually inteligible) belong to a group that excludes English because they have the velar fricative /x/ where English has the older /k/, as in Bav. mocha, Alem. mache vs. English make. So the sound change *k > ch is a shared innovation of the so-called High German dialects.

In other words, we can tell not only which languages are related, but how a group of related languages fits together in a family tree.

The same principles are of course applied to less familiar languages. Several cognate sets in five languages of the Polynesian family are listed in the next table.

| English Gloss |

Tongan | Maori | Samoan | Tahitian | Hawai'ian | |

| 1. bird | manu | manu | manu | manu | manu | |

| 2. fish | ika | ika | i'a | i'a | i'a | |

| 3. to eat | kai | kai | 'ai | 'ai | 'ai | |

| 4. forbidden | tapu | tapu | tapu | tapu | kapu | |

| 5. eye | mata | mata | mata | mata | maka | |

| 6. blood | toto | toto | toto | toto | koko |

We see that no changes happened in the nasal consonants or in the vowels, i.e. all the languages agree. But we can observe in lines 2 and 3 that wherever Tongan and Maori have /k/, Samoan, Tahitian and Hawai'ian have /'/ (glottal stop). Apparently there has been an unconditioned change from /k/ to /'/ in the Eastern branch, or a change from /'/ to /k/ in the Western branch of this family. We choose the first as more likely partly because backing of consonants is more common than fronting (we can think of examples of just this change happening elsewhere, e.g. in Cockney English), and partly because of what we know about the culture history: Polynesia was peopled from west to east, so there was no time when the Western speakers were all in one place without the Easterners.

Next, we see in lines 4 - 6 that there is a systematic correspondence between /t/ in the first four languages and /k/ in the easternmost, Hawai'ian. This looks like another systematic, unconditioned sound change, this time in only one language. (We can see from this example that when English borrowed the Polynesian word for "forbidden", we borrowed it from one of the languages west of Hawaii -- we say "taboo", not "kaboo"). This is what a family tree of the five Polynesian languages would look like, based on the small data set above (the picture is somewhat more complex when we look at other cognate sets):

How far back can we go?

Our methods of reconstructing earlier forms of language are at base little more than educated guesses. Because not all language change is sound change, and certain irregularities creep in, every stage of reconstruction is bound to have a small number of errors. Thus the further back we go, the less certain we can be of our guesses.

Most linguists agree that our methods for reconstruction will take as only as far back as about 5000 - 7000 years; after that, the number of cognate sets available for reconstruction becomes just too low to give results that can be reliably distinguished from chance relationships. Although it would be very satisfying to be able to link up some of the existing families at a higher level, the evidence seems too weak to allow us to do so.

A minority of scholars, however, argue that this is possible, and one particularly well-known group of such scholars goes by the name of Nostraticists, derived from their views that there exists a super-family of language they have called the "Nostratic". A New York Times article from 1995 presents a well-balanced view of the Nostraticist position. Dr. Donald Ringe of the Penn Linguistics Department, himself an expert on the ancient Indo-European language Tocharian and one of the world's leading Indo-Europeanists, is one of the chief critics of the Nostraticist position.

What are the results of language change?

When accompanied by splits of populations, language change results first in dialect divergence (the kinds of differences we see between British and American English; between the French of France and of Quebec; between New World and Old World Spanish and Portuguese).

Initial problems with intelligibility begin long before we would consider talking about separate languages. Indeed, certain systematic comprehension difficulties can occur even within relatively closely related dialects.

For example, the following phrases taken from the spontaneous speech of Chicagoans recorded in the early 1990s were difficult for many non-Chicagoans to understand correctly out of context. In "gating" experiments designed to test cross-dialectal comprehension in American English, subjects first heard a word by itself, then a slightly longer segment, then a whole phrase or sentence that may have disambiguated the original mishearing. These experiments were part of the research project on Cross-Dialectal Comprehension done at the Linguistics Lab here at Penn (for more information on the vowel change called the Northern Cities Shift, which is resonsible for the difference in Chicagoan English that makes it difficult for, say, Philadelphians to understand, see "The Organization of Dialect Diversity" on the home page of the Phonological Atlas of North America .)

| Original segment | Many people misheard as | First expansion | Second expansion |

| drop | ??? (nonsense word containing vowel in "that") | massive drop |

the plane was steady for a while and then it took a massive

drop |

| socks | sacks | y'hadda wear socks | y'hadda wear socks, no sandals |

| block | black | one block | old senior citizens living on one block |

| met | mutt | they met | my parents went to Cuba and that's where they met |

| steady | study | steady for a while | the plane was steady for a while and then it took a massive drop |

| head | had | shook 'er head | this woman in while, who just smiled at her and shook 'er head |

These misunderstandings are based on the fact that the Chicago speakers (along with 40 - 50 million other people in the "Inland North" dialect including Rochester, Buffalo, Detroit, Syracuse, and other cities of that region) have a rotation of their short vowels such that the low unrounded vowel of the "short o" words like drop, socks, block, and hot is being fronted to the position where other American dialects have words like that, hat, black, rap, and sacks, , and where "short e" words like met, steady and head can sound like mutt, study and thud or mat, static and had.

Language Families

Over longer time periods, we see the emergence of separate languages, and, as alluded to above, when a group of languages all descend from a common parent, we call them a family. So we have the family of Romance languages, descended from a form of Vulgar Latin spoken about 2000 years ago, and the family of Germanic languages, descended from an unwritten language called Proto-Germanic, spoken probably in Northern Germany and Southern Scandinavia about 2500 years ago.

As with human families, language families can be joined up to form larger families of more distant relationships. Thus both Germanic and Romance belong to a larger, much older family mentioned above which is known as Indo-European, which was also never written down, but was probably spoken 4,000-8,000 years ago, perhaps on the steppes of Eastern Europe, on the shores of the Black Sea, or somewhere in Anatolia (Asia Minor).

Other subfamilies of the Indo-European family are Celtic (Irish, Welsh, Scots Gaelic), Baltic (Lithuanian, Latvian), Slavic (Russian, Polish, Czech, Serbo-Croatian), Greek, Albanian, Armenian, Indic (Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu and the other modern languages of northern India), Iranian (Avestan, Old Persian, Farsi) and two extinct families, Anatolian (Hittite, Luwian, Lycian) and Tocharian.

Here's one recent view on how the family tree of Indo-European might look, based on a project at Penn that used computational methods to determine what tree best fit the data available. (Note that the nodes of the tree are specific languages rather than sub-families. "Vedic" refers to the oldest form of Sanskrit, and thus represents the position of Indic in the tree.)

The Ethonologue web-page lists 425 modern Indo-European languages.

Of course Indo-European is just one of many language families in the world. This map shows all of the the other major language families of the world, as well as many of the minor families (minor in the sense that they have fewer languages or speakers). Much of the gray territory on this map is the are covered by Indo-European languages.

One might object to some of the details of how the languages are divided up here, but it gives a good general idea.

Languages of the World

So over time, language change and population movement lead to the creation of new languages and the increase of linguistic diversity. Indeed, most scholars think that language probably only arose once, in the original human population that spread out from Eastern Africa 100,000-200,000 years ago. This implies that all modern languages are descended from this original tongue. There is no way for us to prove this, and the supposed original language is way too far back for us to be able to reconstruct it (at least in the opinion of most linguists), but if language is a truly pan-human instinct, then this conclusion is all but forced on us.

Some language stats

This leads us then to consider what sort of language diversity is out there. To begin with, how many languages are spoken in the world today?

The Ethnologue lists 6,809 living languages in the year 2000, with their original locations (to the best of our knowledge) divided geograpically as follows:

| Living Languages | Percentage | |

| The Americas | 1,013 | 15% |

| Africa | 2,058 | 30% |

| Europe | 230 | 3% |

| Asia | 2,197 | 32% |

| The Pacific | 1,311 | 19% |

| TOTAL | 6,809 |

Notice that Europe has quite a small number of languages in this context, though many of them possess disproportionate global influence due to political, social, and cultural history. This is not accidental, but is a direct result of the history of that part of the world, which is filled with large and expansionary empires and nation-states.

In terms of number of speakers, we see a range from Mandarin Chinese, with 874 million native speakers, down to languages with just one known speaker.

A graphical representation of this distribution of sizes can be seen in the figure below, which plots the number of languages with N or more speakers, for N from one to one billion.

Data from the Ethnologue (1999)

The Ethnologue lists 417 languages that are nearly extinct -- those with only a few elderly speakers, and no children learning the language. Dozens of these are Native American languages of the United States.

The following list gives the 20 most populous languages, defined by native speakers. Click on the language name for more detailed figures and other information.

| Rank | Language | Native speakers (in millions) |

| 1 | Mandarin Chinese | 874 |

| 2 | English | 341 |

| 3 | Spanish | 322-358 |

| 4 | Bengali |

207 |

| 5 | Hindi | 181 |

| 6 | Portuguese | 176 |

| 7 | Russian | 167 |

| 8 | Japanese | 125 |

| 9 | German | 100 |

| 10 | Korean | 78 |

| 11 | Wu Chinese | 77 |

| 12 | French | 77 |

| 13 | Javanese | 76 |

| 14 | Yue Chinese (Cantonese) | 71 |

| 15 | Telugu | 70 |

| 16 | Vietnamese | 68 |

| 17 | Marathi | 68 |

| 18 | Tamil | 66 |

| 19 | Turkish | 61 |

| 20 | Urdu | 60 |

These figures exclude second-language speakers, which can be quite significant for some languages. For example, while Hindi has 180 native speakers in India (and over a million in other countries), the number more than doubles to 364 million in India if you include non-native speakers, because Hindi is a lingua franca used throughout India, especially in the North, for communication between people who speak different native languages -- a common situation in a country with so many distinct languages.

In a great many countries across the world, English has official or semi-official status. The Ethnologue lists a total of 508 million speakers, of whom 167 million, or nearly a third, speak it as a second language.

Endangered languages

Many of the 6,000-odd "living" languages cited in Ethnologue are endangered or nearly extinct. Those represented in the left half of the graph above, with 10,000 or fewer speakers, are especially vulnerable.

Roughly half of the world's languages are moribund, in the sense that new generations of children are not being raised to speak them.

Within a century, it is likely that the number of living languages will be cut at least in half, and may well be fewer than 1,000. Thus the current rate of extinction for languages is much greater than the rate of extinction for biological species. Most people believe that this loss of linguistic and cultural diversity is a bad thing.

Language preservation is difficult, but there are some success stories, like the revival of Hebrew in Israel. For languages that can't be saved, it is still possible to document them for scientific purposes and for the sake of future generations who might want to study or even revive them.

For further discussion, see the web sites of the Endangered Language Fund, the Foundation for Endangered Languages and the International Clearing House for Endangered Languages.

Problems of counting

All of the counts cited here are subject to question. One may question the census figures and also (especially in multilingual cases) who counts as a speaker of which language.

For instance, the 1996 edition of Ethnologue cites 266 million native speakers of Spanish.

The 1999 revisions increase the number of native speakers of Spanish to 332 million, moving Spanish past English into second place. This does not represent a 25% population increase in 3 years, nor even a 25% increase in available census data, but rather (apparently) a revision in who is counted as a Spanish speaker.

The 2000 figure gives a range 322-358 million, reflecting different sources or calculations, but the nature of the different counts is unclear.

Another set of questions has to do with the problem we discussed in the first lecture of what counts as a language and what counts as a dialect. For instance, you may be surprised to see Arabic -- certainly one of the world's major languages -- missing entirely from this list of the "top twenty."

In fact, Arabic in all its varieties (35 according to the Ethnologue) has 219 million speakers world-wide, and with this count would be #4 on the list above.

However, Ethnologue considers the local colloquial varieties of Arabic to be separate languages. Here are the largest ones.

| Variety | Native speakers (in millions) |

| Egyptian | 46.3 |

| Algerian | 22.4 |

| Morrocan | 19.5 |

| Upper Egyptian | 18.9 |

| Sudanese | 17.5 |

| Lebanese-Syrian | 15.0 |

| Iraqi | 13.9 |

This classification into separate languages is not unreasonable, since different Arabic colloquials are not mutually intelligible, or at least not entirely so.

Algerian Colloquial Arabic (for instance) is roughly as different from Egyptian Colloquial Arabic as Portuguese is from Spanish.

On the other side of the argument, educated people in all the Arabic-speaking countries can speak, read, and understand "Modern Standard Arabic", which is also the language used in news broadcasts, newspapers, and so on. Thus an educated Egyptian in Algeria can read the paper, understand the TV news, and converse easily with an educated Algerian. In some sense, they remain part of the same linguistic community, in a way that speakers of Spanish and Portuguese may not.

To take another example, Hindi and Urdu are essentially the same language. (The old-fashioned term Hindustani refers to this linguistic unity.) For historical, political and religious reasons, they have different writing systems, and some different strata of borrowed vocabulary, but ordinary speakers are likely to be able to understand one another quite well.

It's the literary versions of the language that are particularly distinct from each other, since they emphasize vocabulary from different traditions -- Sanskrit for Hindi, and Arabic and Persian for Urdu.

It is largely for this reason that the two forms of speech are nowadays typically considered distinct languages. Combining their counts would give us 181+ 60 = 241, which would put the Hindi/Urdu combination into fourth place.

A recent and striking example of a very similar nature is the change in Serbo-Croatian from ten years ago to today. Ten years ago, Serbo-Croatian was most often treated as a single language, documented in single grammars, with single dictionaries.

It was well known that there were two ways of writing it -- with Roman characters in Croatia, and with Cyrillic characters in Serbia -- and that there was a continuum of dialect variation from Serbia in the east to Croatia in the west, with vocabulary differences as well -- but this did not change the obvious "fact" that it was a single language.

Now they are often presented as three languages -- Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian.

This is not just an idle matter of nomenclature -- at least in Croatia and in Serbia, strenuous efforts are underway to purge the language of elements that are felt to reflect pollution from linguistic or cultural elements associated with the other end of the geographical, political, and historical conflict.

"Dialects" again

One commonly cited characterization of this use of the word "dialect" is that a language is a dialect with an army and a navy. This is perhaps cynical, but quite accurate: national boundaries often have as much to do with the use of the terms as the question of mutual intelligibility.

Example 1: The Scandinavian languages (especially Norwegian and Swedish, but also Danish) have a great deal of mutual intelligibility, but since they are associated with different countries, we call them languages.

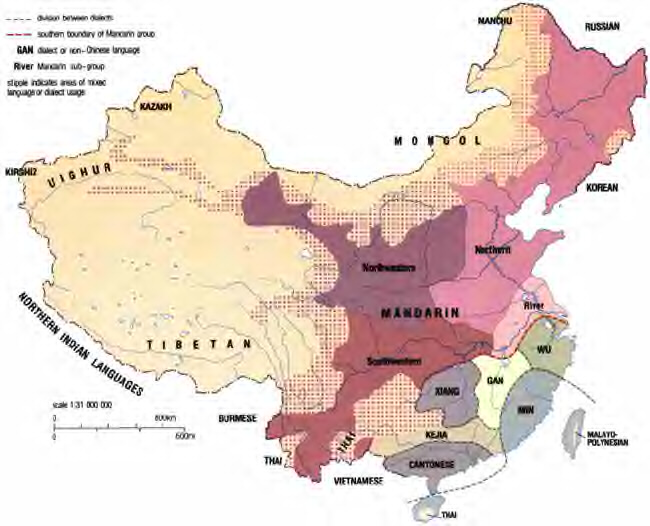

Example 2: Chinese is often called a "language", but in fact consists of at least seven or eight languages with enormous internal dialect variation. (The Min group on this map is usually divided into Northern and Southern.)

There are both political and cultural reasons for treating this as a single linguistic unit, including the unifying character of the writing system which ignores changes in pronunciation of the same word (buth which does not guarantee easy written intelligibility across dialects, given differences in syntax and word choice).

Still, the "dialects" Mandarin (the modern standard, spoken in the central and northern regions) and Cantonese (spoken in the south, including Hong Kong, and in many Chinese communities abroad) are not mutually intelligible. That's why they're listed separately among the 20 most populous languages.

Linguists, and some others, prefer to use the term "the Chinese languages" to reflect this reality.

Because "intelligibility" is a matter of degree, it's often impossible to draw clear lines between languages. This arises particularly in the case of a dialect continuum: adjacent regions can understand each other's speech, but regions further apart may not understand each other, and just because Bob understands Frank, and Frank understands Suzie, we can't assume that Bob will be able to understand Suzie.

In fact, such situations exist all over the world. Some examples in Europe are shown in this map.

Thus while we call Portuguese, Spanish, French, and Italian different languages, the local situation is more gradient. Moving from Portugal to Italy, the local dialect gradually shifts from town to town. The official language in the government and schools may change radically when a border is reached, but the speech in the marketplace may be quite similar on each side of the border. Only with national centralization of education and media is this situation changing.

Similarly, the distinction between German and Dutch is quite clear at the level of standard, literary languages, but in local terms the traditional dialects of northern Germany are very similar to those of the Netherlands.

Even drawing the major dialect difference within Germany is not entirely straightforward. "Low German," spoken in the north, is like Dutch in having stops in certain words where "High German," spoken in the south, has fricatives. The latter is the basis of the standard language. (The terms come from the high or low elevations characteristic of the regions, not from a social judgment.)

| Low German & Dutch | High German | |

| ik | ich | "I" |

| maken | machen | "make" |

| dorp | dorf | "village" (thorp) |

| dat | das | "that" |

It should be clear that, from a strictly linguistic point of view, it is a tricky matter to draw a line between the local varieties of Dutch and Low German, and the situation doesn't get any easier when we try to draw the line between between Low German and High German.

The difficulty in counting languages and the arbitrary decisions that it is based on are demonstrated nicely by the fact that the counts in the Ethnologue change from year to year, not because of population shifts, but because of changes in the counting methods.

See this page for a list of the 50 most populous languages in the world, based on earlier edition of the Ethnologue and therefore slightly different from the list of 20 given above.

You should be able to understand why the following statement, given on that web page, is incoherent from a linguistic point of view:

"Many of the languages listed are technically dialects, not separate languages. They are listed separately because they differ from each other enough to be mutually unintelligible."

Typology

Independent of language family associations, we can characterize languages on various dimensions where correlations among values recur.

Typological classification can be done at any level of linguistic description, but the commonest forms are phonological, morphological and syntactic.

Phonological typologies deal with issues such as

- phoneme inventory

- syllable structure

- prosody

Thus we might ask how many distinct vowels a language has, and how they are arranged; what sorts of syllable-final consonants a language has, if any; whether the language has word-stress, and if so, if its location is predictable from the structure of the word.

In general, the answers to these questions tend to follow predictable patterns. For example, if a language allows stop consonants to occur in syllable-final position -- as in the English word "dip" -- it will generally also allow nasal consonants in the same position -- as in English "dim". It is often helpful to think of these patterns in terms of a hierarchy of more or less "marked" (i.e. unusual or unexpected) configurations. Thus a (very) partial hierarchy of markedness for syllable structures would be

Consonant Vowel >> Consonant Vowel Nasal >> Consonant Vowel Stop

As a rule, a language that has more "marked" patterns also has less marked ones.

In the case of morphology, an old but still useful typological taxonomy refers to languages as isolating (words lack affixes, and grammatical relationships are mainly signaled by word order), inflecting (words are marked with affixes to indicate their grammatical function), agglutinative (words incorporate long sequences of affixal elements), and polysynthetic (whole sentences may be expressed as single words, with several stems and various functional elements expressing their relationship).

The most basic syntactic typology has to do with the normal order of subject, verb and object in simple sentences. English has the order S V O, while Latin has the order S O V:

Kim opened the book.

S V O

Canis felem vidit.

(Dog cat saw)

S O V

There are six possible orders of subject, verb and object, and at least a few of the world's languages exemplify each possibility. However, some orders are more common than others. According to a number of large-scale surveys, SVO and SOV are the most common types, each accounting for about 40% of the world's languages. Perhaps another 10% are VSO, and the remainder are divided up over the other possible types.

There are a series of other implicational universals, many of them discovered in pioneering work by the linguist Joseph Greenberg. These take the form "if X then y". For example, it turns out that, if a language is SVO, then it is overwhelmingly probable that it will have prepositions, while if it is SOV, it is overwhelmingly probably that it will have postpositions. A whole are of linguistic inquiry, known as linguistic typology, is dedicated to approaching issues of language comparison from this point of view.